WesternU’s Austin Lecture examines unintended consequences of COVID-19 mitigation efforts

COVID-19 mitigation strategies were established in March 2020 to decrease viral transmission and to support our health care delivery systems. But these strategies, while necessary, were not without consequences.

These mitigation efforts had a deeply impactful effect on children’s health – most notably through delayed diagnoses, missed vaccinations and a negative impact on mental health, according to the keynote speaker for Western University of Health Sciences’ eighth Dr. Robert L. Austin Endowed Lectureship in Pediatric Medicine, Pharmacology & Health Care Policy.

Oregon Health & Science University Professor of Pediatrics Judy A. Guzman-Cottrill, DO, presented “The Impossible Balancing Act: Protecting our Young from COVID-19 and the Unintended Consequences” at the Austin Lecture, held via Zoom on May 3, 2022.

The U.S. declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals and clinics quickly implemented strict mitigation policies to try to protect patients, visitors, and health care workers, Guzman-Cottrill said. Quickly, facilities became overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) supplies became scarce. Because of this, telehealth rapidly increased across the country. Schools closed and stayed closed in the fall.

“Not all kids had home internet service, video devices, or even space at home for instruction,” Guzman-Cottrill said. “And remember, a lot of these parents, especially of younger school-age children, had to make the hard decision of going to work or staying home and leaving their jobs to be able to be with their children as they tried to learn from home.”

Pandemic-related mitigation strategies in ambulatory settings, clinics and outpatient programs included strict screening processes for staff, patients and visitors.

“As you would guess, this decreased access to care. Many ambulatory care clinics turned to telehealth visits only,” Guzman-Cottrill said. “Because of that, the quality of care for some services diminished via telehealth. One example is mental health. Some children and adults just don’t do as well with telehealth as opposed to sitting in the room with their mental health provider.”

Lack of physical examinations lead to delayed diagnoses, she said.

“When we’re talking to our patients in front of a screen, we cannot touch them. We cannot do a physical exam, so things will get missed,” Guzman-Cottrill said. “When we’re talking to patients over the phone or via telehealth, we’re going to miss some really important diagnoses.”

The four largest pediatric oncology medical centers in Israel – which treat about 500 new cancer patients annually – conducted a study on their 2020 data, listing all the patients who had delayed diagnoses of new cancer because of COVID-related issues, mostly closures.

Some examples include a 5-year-old boy with craniopharyngioma who had an eight-month delay in obtaining a diagnostic MRI due to cancellation of what was thought to be a non-urgent examination, and a 3-year-old girl with metastatic Wilms tumor who had a one-month delay in diagnosis due to the physician’s refusal of imaging for fear of exposing her to COVID-19.

A study published in July 2020 examined the delayed diagnoses of pediatric solid tumors at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in the Bronx, N.Y. In each year from 2015-19, the hospital had eight to 18 new diagnoses from March to May. In 2020, they had only seen four new cases in those months and realized they must have missed cases, Guzman-Cottrill said.

“It was published quickly online in July 2020 as a call to action to pediatricians and other primary care providers and oncologists saying we all have to remember that important, serious new diagnoses in children are going to continue to happen, overlaid on top of this COVID-19 pandemic,” she said.

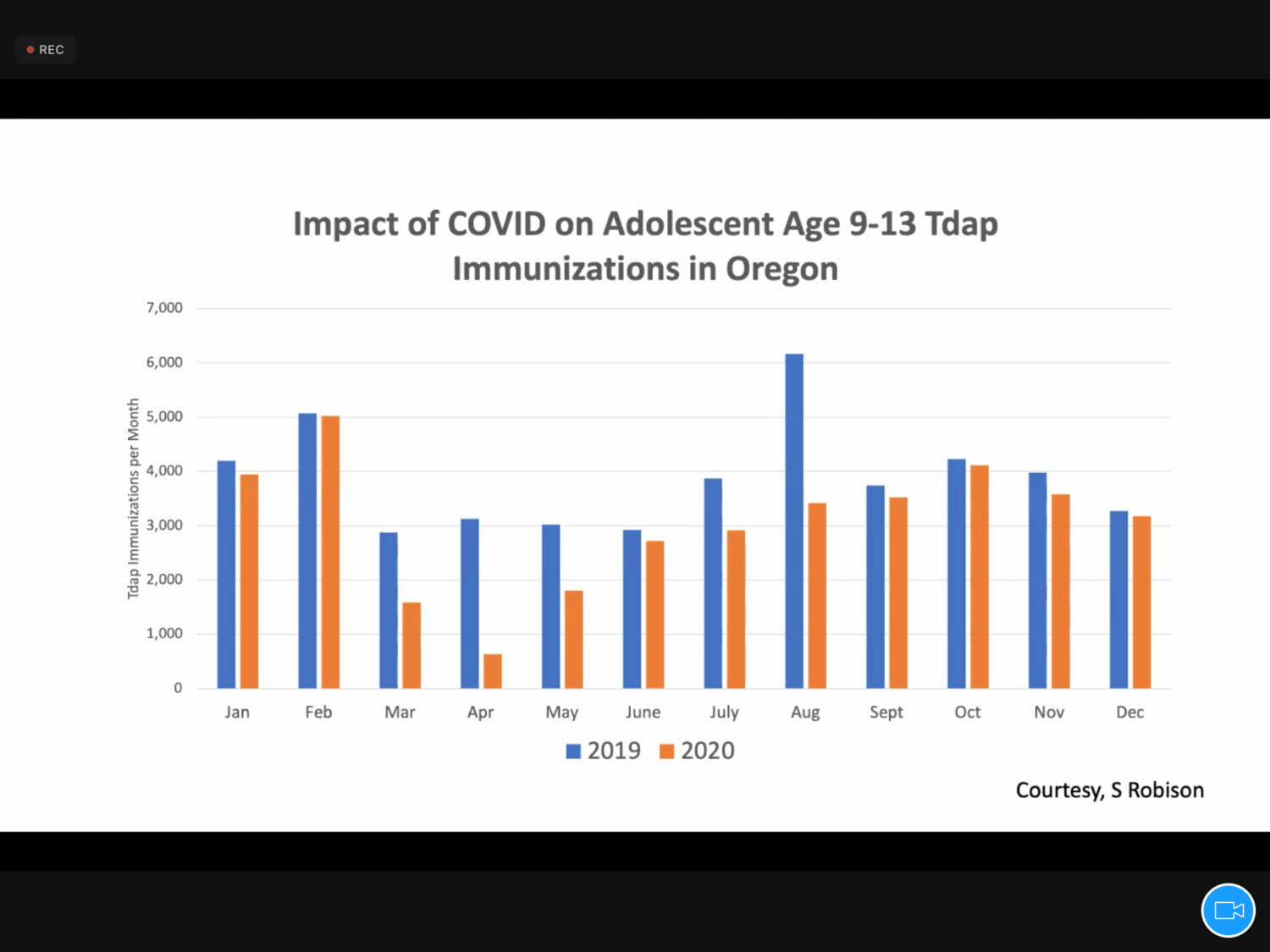

Data from the state of Oregon shows that COVID-19 mitigations greatly affected the number of children receiving regular immunizations for whooping cough, measles and many more vaccine-preventable illnesses.

Oregon data shows in March 2020 when lockdowns began, the number of vaccines went down by almost 500 doses, and never really caught up throughout 2020, Guzman-Cottrill said. Pre-pandemic, each August would have a surge in vaccine doses administered because of back-to-school visits to students’ pediatricians.

“In August and September 2020, kids didn’t go back to the classroom, so we didn’t get that in-person opportunity,” she said.

Guzman-Cottrill urged all health care workers in the audience to ask their patients if their vaccines are up to date, and to vaccinate them before they travel.

“Keep measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases on your differential diagnosis,” she said. “It’s a matter of time. We are going to be seeing more whooping cough, or pertussis, more measles, more chicken pox.”

With the war in Ukraine and refugees moving to other countries, these families will not have access to immunizations for their children. Infectious diseases always take advantage of wartime and refugees, so we have a lot to think about over the upcoming one or two years and beyond in terms of immunizations and all of our risks for vaccine-preventable diseases, Guzman-Cottrill said.

“For all of us health care workers, how can we strategically get kids caught up on vaccines? Flexibility is going to be key. We are going to have to think outside the box. Every office visit is an opportunity. If Johnny comes in with a stomachache, but mom brings Johnny in with his three siblings, look at the vaccine records of Johnny and all those siblings that are sitting there too. If they are overdue for vaccines, get those vaccines into those arms,” she said.

Every inpatient hospitalization is also an opportunity to get kids’ and adults’ vaccines caught up, Guzman-Cottrill said.

“You want to review patient’s vaccines on admission, see what they’ve missed and give those vaccines on the day of discharge if there’s no contraindication,” she said. “And for those of you in primary care, please promote vaccine catch up days this summer and into the fall.”

Closing schools in 2020 helped protect immunocompromised children and those with chronic conditions. But this isolation also took a toll on the mental health of children.

The Kaiser Family Foundation surveyed parents about the past two years of the pandemic. Half of the parents said it had a negative impact on their own mental health. Sixty-three percent of parents said it had a negative impact on their children’s education and 55% of parents said it had a negative impact on their children’s mental health.

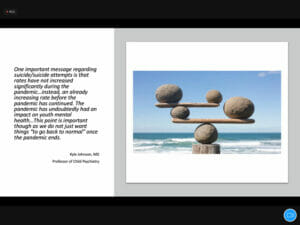

A look at the weekly number of emergency department visits for mental health conditions among children and adolescents show the numbers were already too high for our children in this country, even before the pandemic started, Guzman-Cottrill said. Suicide and suicide attempt rates have not increased significantly during the pandemic.

Guzman-Cottrill quoted her colleague, Professor of Child Psychiatry Kyle Johnson, MD, who said, “One important message regarding suicide/suicide attempts is that rates have not increased significantly during the pandemic…instead, an already increasing rate before the pandemic has continued. The pandemic has undoubtedly had an impact on youth mental health…This point is important though as we do not just want things ‘to go back to normal’ once the pandemic ends.”

Guzman-Cottrill quoted her colleague, Professor of Child Psychiatry Kyle Johnson, MD, who said, “One important message regarding suicide/suicide attempts is that rates have not increased significantly during the pandemic…instead, an already increasing rate before the pandemic has continued. The pandemic has undoubtedly had an impact on youth mental health…This point is important though as we do not just want things ‘to go back to normal’ once the pandemic ends.”

Guzman-Cottrill showed video interviews with teenagers and their parents who shared their stories of dealing with chronic illness and depression amid the pandemic. Miles, 17, suffered a major depressive episode that led to a suicide attempt in February 2020. He talked about going in and out of an intensive outpatient program for mental health and how remote learning helped him avoid the peer pressure and drama that comes with high school. In the end, he said he feels like he’s in a much better place than before the pandemic, with a great group of friends and a better ability to control his environment. He’s happy to be alive. Guzman-Cottrill revealed that Miles is her son.

“So everyone, please take care of yourselves. Take care of your loved ones,” she said. “It takes a village to raise a child. And please be part of that village whenever possible.”

The Dr. Robert L. Austin Endowed Lectureship in Pediatric Medicine and Pediatric Health Care Policy is made possible by a generous donation from Mrs. Gloria L. Austin of La Mirada, California in memory of her husband, Robert, a pediatrician and early supporter of the University. In addition to the lecture, the endowment provides funds for annual scholarships for both an osteopathic medical student and a pharmacy student.

At the beginning of the lecture, WesternU President Robin Farias-Eisner, MD, PhD, MBA, introduced Dr. Guzman-Cottrill. WesternU College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific Assistant Dean and Chair of the Austin Lectureship Committee Lisa Warren, DO ’01, welcomed members of the Austin family who joined the lecture via Zoom.

“From all of us at WesternU, we extend our sincere gratitude to your family for all the ongoing support of our students and our mission. Your impact is felt throughout our classrooms, patient care centers, and in the community that benefit from the knowledge and resources provided by your contributions,” Warren said. “For those of you watching online it is our hope that you leave this lecture inspired, invigorated, and ready to continue taking on the challenge ahead in health care. Your involvement in the WesternU community is critical to our continued growth, success and recognition as a leading health professions university.”